How much do falconers get paid?

For the vast majority of practitioners, falconry is a regulated field sport and a passionate hobby that costs money rather than generates it; however, professional falconers who turn this skill into a career—specifically in the field of bird abatement—can earn a respectable living. The most common source of income is working for abatement companies that contract with vineyards, landfills, resorts, and airports to scare away nuisance birds like seagulls, pigeons, and starlings. Entry-level falconers in these roles typically earn hourly wages ranging from $18 to $30, putting annual salaries between $40,000 and $60,000. Experienced contractors or independent business owners who secure their own contracts can command significantly higher fees, often charging day rates of $500 to $1,000 per site. In high-stakes environments like international airports where bird strikes pose safety risks, contracts can be lucrative, potentially pushing gross revenue for a successful abatement business over $100,000 annually, though this requires years of experience and a fleet of trained raptors.

It is crucial to understand that these higher earning figures represent gross revenue rather than take-home profit, as the overhead costs in professional falconry are substantial. A professional falconer is essentially running a business that requires significant investment in specialized equipment, telemetry systems, transport vehicles, and expensive liability insurance, not to mention the year-round cost of high-quality food, housing (mews), and veterinary care for multiple birds. Aside from abatement, other income streams are limited and generally lower-paying; these include performing educational bird-of-prey shows for schools and zoos, breeding raptors (which is highly regulated and often low-margin), or manufacturing gear like hoods and gloves. Therefore, while it is possible to make a career out of falconry, it is rarely a “get rich quick” profession, and the highest earners are almost exclusively those who master the business side of nuisance wildlife control rather than just the sport of hunting.

Do falconers make good money?

For the vast majority of practitioners, falconry is a regulated field sport and a passionate hobby that costs money rather than generates it; however, professional falconers who turn this skill into a career—specifically in the field of bird abatement—can earn a respectable living. The most common source of income is working for abatement companies that contract with vineyards, landfills, resorts, and airports to scare away nuisance birds like seagulls, pigeons, and starlings. Entry-level falconers in these roles typically earn hourly wages ranging from $18 to $30, putting annual salaries between $40,000 and $60,000. Experienced contractors or independent business owners who secure their own contracts can command significantly higher fees, often charging day rates of $500 to $1,000 per site. In high-stakes environments like international airports where bird strikes pose safety risks, contracts can be lucrative, potentially pushing gross revenue for a successful abatement business over $100,000 annually, though this requires years of experience and a fleet of trained raptors.

It is crucial to understand that these higher earning figures represent gross revenue rather than take-home profit, as the overhead costs in professional falconry are substantial.1 A professional falconer is essentially running a business that requires significant investment in specialized equipment, telemetry systems, transport vehicles, and expensive liability insurance, not to mention the year-round cost of high-quality food, housing (mews), and veterinary care for multiple birds. Aside from abatement, other income streams are limited and generally lower-paying; these include performing educational bird-of-prey shows for schools and zoos, breeding raptors (which is highly regulated and often low-margin), or manufacturing gear like hoods and gloves. Therefore, while it is possible to make a career out of falconry, it is rarely a “get rich quick” profession, and the highest earners are almost exclusively those who master the business side of nuisance wildlife control rather than just the sport of hunting.

How many years does it take to become a falconers?

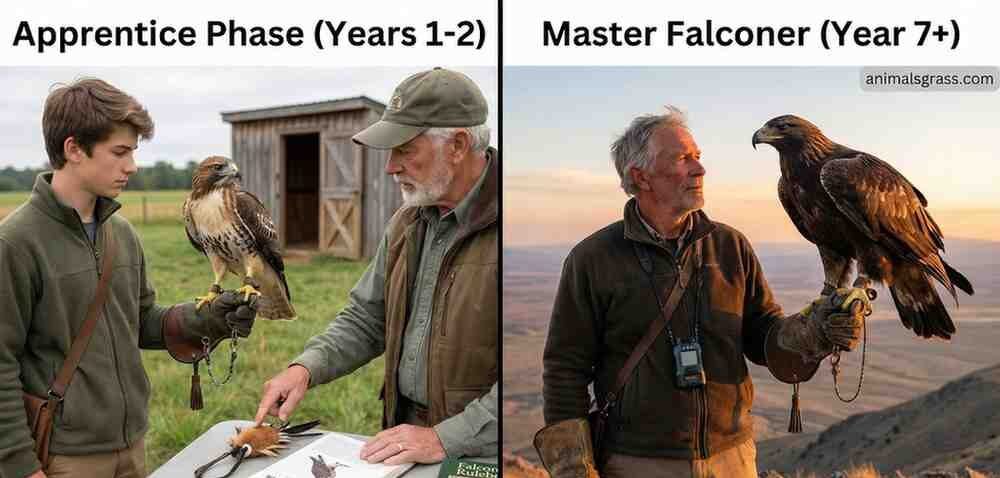

Becoming a licensed and independent falconer typically takes a minimum of two years. In most regions, particularly the United States, you must begin as an Apprentice Falconer, a phase that requires you to train under the supervision of a sponsor (a General or Master class falconer) for at least two years. During this time, you are legally required to house, man, and hunt with a raptor—usually a Red-tailed Hawk or American Kestrel—while also passing a comprehensive written exam and having your facilities (mews) inspected by state wildlife officials. You are not considered a fully independent falconer until you have completed this mentorship and upgraded your permit to the “General” class.

To reach the highest level of the sport, known as a Master Falconer, the process takes a minimum of seven years in total. After finishing the two-year apprenticeship, you must practice as a General Falconer for at least five years before you are eligible to apply for Master status. This advanced rank allows you to possess more birds and access a wider variety of species, including eagles. However, most practitioners view falconry not as a degree to be earned in a set number of years, but as a lifelong lifestyle that requires daily dedication to the bird’s health, training, and hunting needs long after the initial licensing phase is over.

Is falconry a full-time job?

For the overwhelming majority of practitioners, falconry is not a paid job but rather a demanding lifestyle that operates like a full-time unpaid profession. It requires a 365-day-a-year commitment to the bird’s health, husbandry, and hunting needs, often demanding hours of daily interaction that must be balanced around a regular career.1 Because laws in most countries strictly prohibit the sale of wild game caught by raptors and ban the use of falconry birds for general commercial entertainment, most falconers spend thousands of dollars annually on food, equipment, and permits without ever seeing a financial return.

However, falconry can become a legitimate full-time career for those who specialize in bird abatement, a commercial service where trained raptors are used to scare away nuisance flocks from airports, vineyards, and landfill sites. In this specific sector, professional falconers are hired as contractors or employees to work long hours patrolling sensitive areas to prevent bird strikes or crop damage. While this allows one to work with birds all day, it shifts the dynamic from the leisurely pursuit of wild game to a structured, high-pressure business operation that requires commercial insurance, specialized permits, and a fleet of reliable birds to maintain constant coverage.

How long do falconers keep their birds?

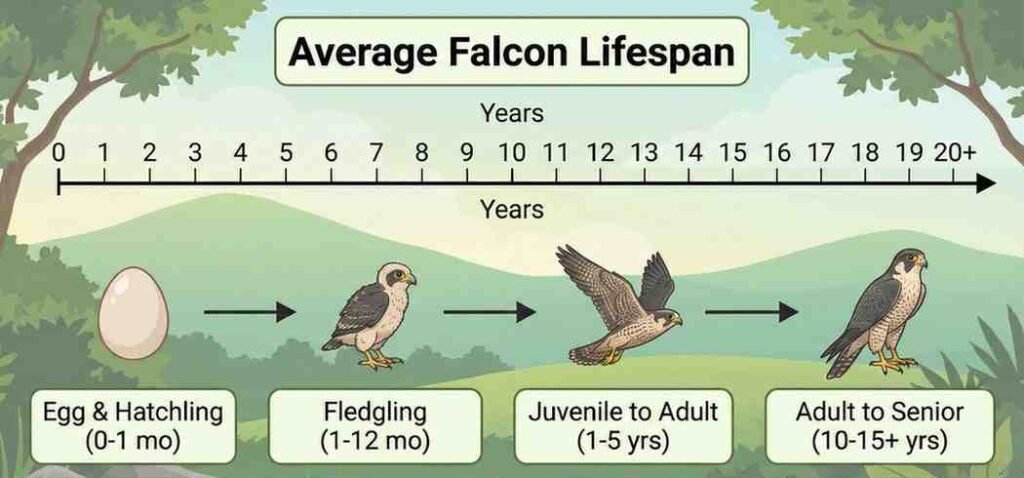

Falconers who fly wild-caught raptors—known as “passage” birds—often follow a practice of “catch and release,” keeping the bird for only one or two hunting seasons. In the United States, for instance, it is common for an apprentice to trap a juvenile Red-tailed Hawk or American Kestrel in the autumn, hunt with it through the difficult winter months to ensure it remains well-fed, and then release it back into the wild in the spring. This traditional method allows the bird to survive its most critical first year with human assistance before returning to the breeding population in peak physical condition, often with superior survival skills compared to its entirely wild counterparts.1

In contrast, captive-bred raptors or exotic species are almost invariably a lifetime commitment, as they generally cannot be released into the wild due to a lack of natural survival instincts or regulations preventing the introduction of non-native species. Because these birds do not have the option of “returning to nature,” they remain with the falconer for their entire natural lifespan, which can be substantial; large falcons and eagles can live for 20 to 30 years in captivity.2 Consequently, acquiring a captive-bred bird is a decision comparable to buying a horse, requiring decades of daily care, veterinary costs, and interaction until the bird eventually passes away from old age.

What is the highest paying wildlife job?

The single highest-paying hands-on career in the wildlife industry is typically that of a Wildlife Veterinarian. These specialized medical professionals are responsible for the health, surgery, and rehabilitation of undomesticated animals, ranging from injured raptors to zoo elephants. Because this role requires a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) degree plus additional residency training in zoological medicine, the barrier to entry is extremely high, and so is the compensation. While entry-level salaries may start around $80,000, experienced wildlife veterinarians working for major zoos, government agencies, or research institutions often earn between $115,000 and $170,000 annually, with top experts in the field commanding salaries upwards of $200,000.

Another top-tier earner in the sector is the Conservation Director or Chief Executive Officer of a major wildlife non-profit organization. While not always in the field handling animals, these high-level management roles involve overseeing large-scale preservation projects, securing multi-million dollar grants, and navigating international wildlife policy. Professionals in these executive positions at large organizations (like the WWF or Audubon Society) frequently earn base salaries ranging from $130,000 to $250,000. However, unlike the veterinary path which relies on medical expertise, these roles require decades of experience in fundraising, politics, and business administration.