What is the controversy with falconry?

The controversy surrounding falconry stems from the tension between preserving an ancient cultural heritage and addressing modern concerns regarding animal welfare and conservation. Critics argue that trapping wild raptors disrupts ecosystems and that the high demand for prestige birds fuels a lucrative illegal black market that threatens endangered species, particularly in the Middle East. Additionally, ethical concerns are raised about keeping far-ranging predators in captivity, the perceived cruelty of using live bait for training, and the ecological risk of escaped hybrid birds genetically polluting wild populations. Conversely, proponents defend the practice as a sustainable partnership that has historically driven major conservation successes—such as the recovery of the Peregrine Falcon—arguing that regulated falconry actually protects raptor populations and increases survival rates compared to the wild.

Is falconry bad for birds?

Falconry is not inherently bad for birds and, when practiced ethically, often provides a significantly safer and easier existence than the wild, where mortality rates for juvenile raptors can exceed 70% in the first year due to starvation and disease. A captive falcon under the care of a responsible falconer benefits from a consistent diet, shelter, and veterinary attention, often living twice as long as its wild counterparts while maintaining physical fitness through free flight. Since the sport relies on the bird choosing to return to the gloved hand after being untethered, the relationship is necessarily built on trust and positive reinforcement rather than coercion. However, the practice can become harmful if it involves inexperienced handling, neglectful husbandry, or contributes to the illegal black market trade, meaning the impact on the bird depends entirely on the competence and ethics of the human involved.

Why do Arabs like falcons?

Arabs cherish falcons because the bird is a powerful living link to their ancestral Bedouin heritage, representing survival, nobility, and status. Historically, in the harsh desert environment where food was scarce, falcons were not kept as pets but were essential partners used to hunt elusive game like hares and Houbara bustards to sustain the tribe. This ancient reliance forged a deep spiritual bond based on trust and patience, virtues highly valued in Arab culture. Today, while no longer needed for survival, falconry has evolved into a prestigious “sport of kings” and a national symbol of pride, with elite falcons serving as status symbols that connect modern Arabs—often in luxury settings—back to the rugged traditions and freedom of their forefathers.

Why do Arabs keep falcons?

Arabs keep falcons as a profound way to honor their Bedouin ancestors and preserve a cultural identity that values patience, honor, and survival.1 Originally, keeping a falcon was not a luxury but a necessity for desert tribes who relied on the birds to hunt meat in an arid landscape where food was scarce.2 Today, this tradition has transformed into a prestigious national pastime and status symbol, with falcons treated as family members and often granted their own passports for travel.3 Beyond the display of wealth, keeping these birds maintains a spiritual connection to the desert heritage, teaching younger generations the ancient skills of handling, training, and respecting nature in a rapidly modernizing world.4

Why do not falconry birds fly away?

Falconry birds actually can fly away at any moment, but they choose to return primarily due to positive reinforcement and a bond based on food security rather than affection.1 The core of this training is “weight management,” where the bird is flown at a specific weight where it is healthy and strong but keen enough to hunt, understanding that the falconer is its most reliable partner for food. Through repetitive training, the bird learns that returning to the glove or lure results in an easy, guaranteed meal, making the falconer a valuable asset rather than a captor.2 While the risk of a bird being lost to high winds or chasing prey too far always exists (which is why modern falconers use GPS telemetry), the bird stays because it associates the falconer with safety and success, not because it is forced to.

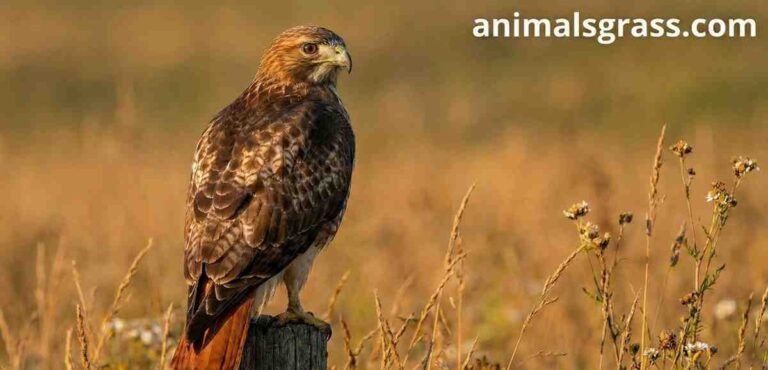

Could a hawk pick up a 20 pound dog?

No, a hawk cannot pick up a 20-pound dog. It is physically impossible for even the largest hawks, such as the Red-tailed Hawk (which weighs only 2 to 4 pounds), to lift an animal that heavy. Hawks can typically only carry prey that weighs less than their own body weight—usually around 1 to 3 pounds—meaning a 20-pound dog outweighs the bird by nearly ten times. While a hawk might swoop down and injure a dog of that size if it feels threatened or desperate, it would be unable to lift it off the ground; the real “lifting” danger exists only for very small pets (under 5 pounds) and usually comes from much larger raptors like Great Horned Owls or Golden Eagles, not common backyard hawks.

How much money do falconers make a year?

Most falconers earn nothing from the sport, as it is primarily a regulated passion that costs thousands of dollars annually in equipment, food, and permits; however, professional falconers working in “bird abatement” can earn between $30,000 and $60,000 per year, with successful business owners earning over $100,000. While the vast majority of practitioners are hobbyists who lose money maintaining their birds, a small niche of professionals are hired by airports, vineyards, and resorts to use their hawks and falcons to scare away pest birds. Additionally, highly skilled trainers working in the Middle East’s prestigious falconry industry or for large breeding projects can command higher salaries, but for the average person, falconry is a lifestyle expense rather than a source of income.

What is the cultural significance of falconry?

Falconry holds immense cultural significance as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage that connects modern societies to their ancestral roots, symbolizing nobility, patience, and a deep respect for nature. Originating as a survival necessity for Bedouin tribes and Central Asian nomads who relied on raptors to hunt food in harsh environments, it has evolved into a prestigious tradition often called the “sport of kings,” serving as a badge of national identity and status in the Middle East and Europe. Beyond its historical utility, the practice fosters a unique interspecies bond where the bird is a partner rather than a pet, helping to preserve ancient vocabulary, craftsmanship, and ecological knowledge that might otherwise be lost in the digital age.